Technical Debt Is Not the Enemy

Every engineer complains about tech debt. Most of them are wrong about what to do about it.

Every engineer complains about tech debt. Most of them are wrong about what to do about it.

"We need to stop everything and pay down tech debt."

I've heard this a hundred times. Usually from engineers frustrated with messy code. Sometimes they're right. Usually they're not.

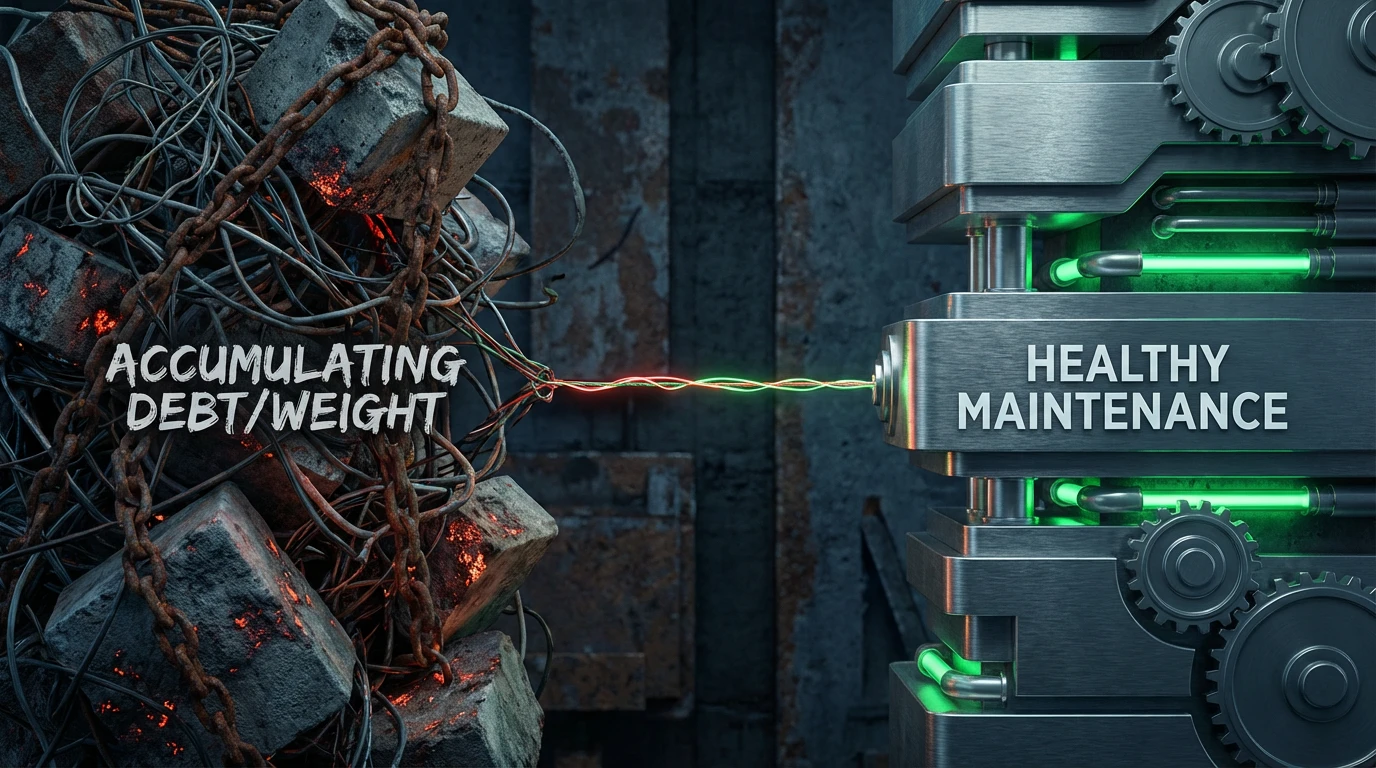

Technical debt isn't inherently bad. It's a tool. Like actual debt — sometimes it makes sense to take it on, sometimes it doesn't.

Ward Cunningham coined the term. His original meaning: shipping something you know isn't ideal to learn faster, then coming back to fix it once you understand the problem better.

That's strategic debt. You're trading future cleanup for present learning.

What most people call tech debt:

Some of this is debt. Some of it is just... code. Old code isn't automatically debt.

Good debt:

Bad debt:

The first kind is a business decision. The second kind is dysfunction.

I've intentionally shipped suboptimal code in these situations:

Racing a competitor. Being second to market with perfect code is worse than being first with decent code.

Validating an idea. Building a polished system for a feature nobody wants is waste. Build ugly, learn if it matters, then polish.

Regulatory deadline. Ship the compliant version now, refactor later.

Team capacity crunch. Sometimes you need to get through the quarter with what you have.

The key: know you're taking on debt and plan to pay it.

"We'll clean this up later" without a plan is not strategy. It's denial.

Not "whenever engineers want to." That's how you end up with perpetual refactoring that ships nothing.

Pay down debt when:

It's actively slowing you down. Can't add features without breaking things? Debt is costing more than paydown would.

It's causing incidents. If the same janky system causes outages repeatedly, fix it.

You're about to build on top of it. Taking new debt on top of old debt compounds the interest.

You have natural downtime. Between major initiatives, use the slack for cleanup.

Not all debt is equal. I use a simple framework:

| Debt Type | Priority | Reason |

|---|---|---|

| Causing incidents | High | Direct business impact |

| Blocking features | High | Slowing roadmap |

| Increasing dev time | Medium | Indirect cost |

| Aesthetically annoying | Low | Not actually hurting anything |

That last category is important. Code that's ugly but working is not urgent. Engineers hate hearing this, but it's true.

"This code is embarrassing" is not a business justification.

Some teams do "20% for tech debt." It sounds nice. In practice:

Problems:

What works better:

Debt paydown should be treated as seriously as feature work. That means planning, justification, and measurement. (This is essentially Developer Experience as Product Work.)

My favorite approach for big debt: don't rewrite, strangle.

Instead of replacing the old system wholesale:

Lower risk. Incremental progress. You can stop halfway if priorities change.

Big bang rewrites fail constantly. Strangler pattern works.

When engineers say "we need to address tech debt," I ask:

If they can't answer these, it's not a proposal. It's a complaint.

When the answers are solid, I prioritize it against other work. Sometimes debt wins. Sometimes features win. That's normal.

Most debt conversations are actually about something else:

These are real problems. But "rewrite everything" isn't the solution.

Listen to what engineers are actually saying. Address the underlying issues. The debt conversation often resolves itself.

Technical debt is a tool, not a sin. Take it deliberately, track it honestly, pay it strategically. The goal isn't zero debt — it's debt that's serving business goals rather than accumulating invisibly.